Emotional Intelligence in Teams; A look at Self Awareness.

By

Gillian Gathoni Mwaura

Building a team begins

with understanding the task. After which, one identifies and enlists the

members to give the team the best opportunity to fulfill its purpose (Griffith

2015, 29). In his book titled Good to great, Collins (2001)

argues that the “who” question comes before the “what” question. Great

leaders begin by getting the right people on and the wrong ones off the bus (Collins

2001, 63).

The author of this paper’s team formation experiences has not presented her with opportunities to choose the right people for a team; on the other hand, most of her teams are coincidental. The author is mainly involved in Sacrifice Reliant Organizations (SRO). SROs are organizations whose structures are oblivious and ambivalence of calling. They are primarily under-resourced, therefore unable to attract talent-based people but attract people who generally feel “called” (Anastasiadis & Zeyen 2021,13). The leadership of such coincidental teams may not involve throwing wrong people out of the bus but perhaps developing individuals and a team that can work together. Instead of turning away from others who are “wrong,” members must turn towards each other and believe they can form the right team. This paper explores self and group awareness as an essential part of Emotional intelligence (EQ). The author will also dialogue with one of the healthy teams she has observed lately.

Emotional Intelligence

Emotional intelligence

(EQ) is the ability to perceive and express emotions, use emotions to facilitate

thinking, understand the reason with emotions, and effectively manage emotions

within oneself and in relationships with others (Salovey, Meyer 1990 189).

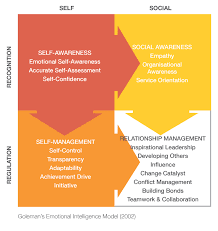

Goleman (2002) refers to EQ as one’s competence in understanding their own (self) and other people’s emotions (social) and the ability to cope effectively. He argues that EQ has four domains (Goleman 1995, 43):

a) Self-awareness- This is

one’s ability to know their own emotions.

b) Self-management- This is the ability to hold

one’s feelings appropriately.

c) Social awareness: This is the ability to be

more attuned to subtle social signals that indicate what others need (empathy).

d) Relationship management -This is one’s ability

to manage emotions in others.

Goleman (1995) argues that EQ and

other intelligence are not opposing competencies but rather separate ones (43).

Mason (2012), on the other hand, argues that managing

a team requires greater EQ than other cognitive intelligence (Mason 2012, 5).

Unlike cognitive ability, Mason (2012) says

that testing EQ has not enjoyed much support over time but is considered “elusive,”

and there has been considerable debate surrounding the psychometric properties

of existing measures. Even amidst their

reservations, he states that researchers seem to agree that a critical

component of EQ involves self-awareness of moods, emotions, feelings, strengths,

and weaknesses (Mason 2012, 5).

Self-Awareness

Griffith argues that one

of the main influences on interpersonal dynamics is the emotional and social

maturity of the team and the leaders. He suggests that emotional intelligence

is critical to teams, just like cognitive intelligence. Griffith demonstrates

how the most effective team members are those who can recognize and regulate

their own emotions in turn for others (Griffith

2015, 60–61).

Goleman introduces the

term self-awareness in the sense of ongoing attention to one’s internal state.

He argues that self-awareness is not attention that gets carried away by

emotions, overacting and amplifying what is perceived. Rather it is a neutral

mode that maintains self-reflectiveness even amidst turbulent emotions. Self-awareness

acts like our guide in fine-tuning work-related social skills and team management. One

becomes self-aware when they have clarity about emotions that undergird them

and are in a good psychological state to tend to the situation. (Goleman

1997,46- 48).

At the formation stage of a team, members must

discover who they are and who others are in a team. Katzenbach (2005)

argues that team performance is a function of what its members do as

individuals (Katzenbach 2005, 164).

One of the strategies in

developing EQ is exposing members to Emotional Quotient (EQ) tests which

measure an individual’s ability to recognize their own emotions and others

which influences their behavior and speech. Emotional Quotient tests are

usually personality-based. Research has argued that personality differences are

not measurable (quantitative) but primarily qualitative. Mason (2012),

therefore, argues that personalities should be studied and described but not

tested (Mason 2012, 6).

Team self-awareness

Emotional intelligence

is not only beneficial for individuals. Much research has been done on EQ on

performance in teams. The premise for linking EQ to team performance argued

that high EQ enables team members to manage and be aware of their own emotions

and the emotions of other team members. When team members begin to

practice self-awareness, noticing the group’s mood and needs, members respond

to one another with empathy. Goleman (2002) argues that showing empathy leads

the team to create and sustain positive norms and manage its relationships with

the outside world more effectively. Social awareness- especially empathy, at a

team level, is the foundation that enables a team to build and maintain effective

relationships with the rest of the organization. Members of a team express

their self-awareness by being mindful of shared moods and the emotions of the

individuals within the group. Goleman also notes that emotions are contagious,

and team members take their emotional cues from each other, for better or for

worse (Goleman 2002, 59).

Team self-awareness

requires team members to be self-aware and be attuned to the emotional

undercurrents of individuals and the group. If a group lacks emotional intelligence,

they cannot discern individual feelings, setting a chain reaction to the whole

team. On the other hand, a team with group emotional intelligence can recognize

and confront such individual distress and hijack the group.

A

Biblical Understanding of Emotions.

This session will review EQ

through a Creation, Fall, Redemption, Restoration Framework. In the beginning,

God created man uniquely in his image and likeness (Genesis 1: 26-27, Isaiah

64:8). Different people have different social and emotional traits, making them

have specific personalities. God creates this diversity and appreciates his

creation. Throughout scripture, we encounter a God who though transcendent, is

personal and interacts with the created. He loves his creation, and his actions

towards them are consistent with his dependence and immutability (James 1:17).

Human beings deserve consistent and unconditional love (1st John

3:16) because they have value and are created in the image of God (Genesis

1:26-27; 9:5-6). Our emotions reflect our creator, who understands them and

will never change how he feels about his creation. As the creator, God’s emotions

are central to his personality, not a projection of human attributes of

emotions (1st Timothy 2:4, Psalms 11:5-7). His emotions are not

dependent on outside forces but flow from his personhood (Malachi 3:6, James

1:17). For example, Human anger is subjective and volatile, but his anger is

rooted in his justice (James 1:20, Proverbs 14:19; 15:18).

Because of sin, both our human view of emotions

and our view of God’s emotions are distorted but not beyond restoration (Psalm

51:5; Romans 5:12). Humanity, therefore, cannot save itself through its wisdom,

choice, and goodness but needs a savior (Romans 3:23; 6:23;12:2). God is

in the process of redeeming his image in human beings through Jesus Christ so

we can reflect his essential qualities. Human beings whose image is restored become

image bearers who participate with God in restoring His image in the distorted

human beings. Their view of themselves and others is subjected to the Holy

Spirit’s role, who develops them to Christlikeness. Emotions are part of what

needs redemption and will be restored at the new creation. Emotions will be

part of heaven (Revelations 6:10, 7:10). God will wipe away every tear from our

eyes, and there will be no more sorrows. There will be singing, rejoicing, and

tears of joy in the heavenly feast (Luke 6:21).

Self-Efficacy in Emotional Intelligence.

Bandura

(1977) defined

self-efficacy as an individual’s

capacity and confidence to execute or control motivation and behavior necessary

to produce specific performance attainments. Bandura’s social cognitive theory and social

learning led him to conclude that people can control their behavior through “self-regulation.”

He argues that introspection of one’s thoughts and feelings motivates

individuals to achieve set goals and behavior change (Bandura 1977,193). Mayer also argues that

human beings can motivate their behavior constructively when their EQ is high (Mayer

and Salovey 1997, 532).

When posed with a

question, “how do you maintain a healthy team”? The interviewees each mentioned

their dependence on the Holy Spirit in helping them love each other well and be

patient with one another. Self-efficacy seems to point us to having faith in

ourselves and managing our behaviors. The interviewees all agreed that it is crucial

to be self-aware and aware of others, but the ability to have a healthy team is

enabled by submitting to one another. One of the interviewees quoted, “the call

for Christians is to die to self and be born again- born into eternal life. We

no longer live, but Christ lives in us” (Galatians 2:20). Our faith, therefore,

must be Christ who enables us to become Christlike. Individuals and team members must be aware that

not all personality traits they have are accurate. Therefore, individuals

need to analyze the underlying assumptions of their personalities. Individuals

must discern what influences their personalities and which traits need

redemption. The Holy Spirit is essential in the analyzes since He is the

one that sheds light on dark corners. It

will also be only through the Holy Spirit that human beings can understand the

complexity of who they are and entrust themselves to the Holy Spirit’s power in

shaping their personalities. This process of self-awareness is a life journey that

becomes part of our formation and must be done from belonging. We belong to Him,

and therefore we can take time responding to ways in which he shapes us. We do

not belong because of some personal traits we carry.

Human beings require a

root change for any fruit change. They require abiding in Christ and Him

abiding in them to bear much fruit that will last long. We can do nothing about

parts of our personalities that need redemption without abiding. When we abide,

we put off the old self, which is being corrupted by its deceitful desires; and

are made new in our minds’ attitude and put on the new self-created to be like

God in true righteousness and holiness (Ephesians 4:33-24).

Healthy teams require healthy individuals. Some of the habits of healthy teams mentioned by the interviews

and generated from

personal experience and diverse authors are:

Listening- For any team to

function well, it is essential to listen to each other. Colwill (2015), talking about dialogue, argues

that listening requires deliberately focused attention on what others are

saying; it is the discipline to remain quiet while others speak and then ask follow-up

questions that draw out the meaning of others. She calls it deep listening

-an act of love (Colwill 2015, 3). When team members are self-aware and have team

self-awareness, they create an environment that allows each perspective to be present,

including that of a lone dissenter, before a decision is made.

Feedback- In addition to listening, team members must

learn how to respond constructively to views expressed by others by giving

feedback. Goleman calls it “providing feedback” (Goleman 2002,57 ). From the

observations made from the interviewees’ team dynamics, there seems to be

honesty with each other and a redemptive environment. Through such an environment,

there is lots of formation that happens.

Empathy- Goleman says that an

emotionally intelligent team has the collective equivalent of empathy, the

basis of all relational skills. Goleman explains how being empathetic does not

mean being nice, but it means figuring out what the whole system needs and

going after it to make all involved more successful and satisfied with the

outcomes (Goleman 2002, 62). In such an environment, questions are freely

asked and genuinely answered. Such teams are aware that they can be vulnerable

and still loved and cared. Colwill (2015) argues that it is essential to have

people speak authentically about what is important to them yet maintain

awareness of others and their opinions in dialogue. She refers to it as voicing

and says it requires honesty even if the view to be expressed is a dissenting

one (Colwill 2015, 4). “Diversity has a seat at the table; inclusion has

a voice at the table, and belonging is having that voice heard” Liz Fosslien.

Suspending- Colwill (2015) says

that there has to be suspending in dialogue, which involves self-control in

delaying one’s hasty judgments of other persons, their opinions, or behaviors (Colwill

2015, 4).

Some EQ tests have stereotyped some traits and personalities, and teams must

learn to look at each other as God looks at them. Help each other identify

areas where they could prayerfully trust God for redemption.

Ground rules -Ground rules in a team

include establishing norms and maximizing harmony to ensure that the team

benefits from the best talents of each member. Best leaders pay attention and

act on their sense of what is going on in the group, and they need not be

obvious about it (Goleman 2002, 58). These norms are similar to Gratton’s

signature relationship practices. Group guiding habits defining the terms of

engagement Leaders have a significant role in modeling behaviors followed in

the team as the norm. Gratton shares an example that at companies where

leaders demonstrate collaborative behaviors, teams collaborate well (Graton

2007,104)

Whole Group attention - Because teams behave differently

at different points, as Bruce Tackman suggests (Forming, Storming, Norming, and

performing), leaders should create ways for members to talk about problematic

issues in each season.

Conclusion

Our

becoming Christlike means that we are getting clothed with compassion, kindness,

humility, gentleness, and patience of Christ (Colossians 3:13) as our Lord

Jesus. As a result of abiding in him, we bear much fruit ;Love, joy, peace, patience,

kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self (Galatians 20:22-23). When individuals in teams bear the

fruit seen above, how they relate to one another promotes an environment full

of grace and believes that God changes people. These fruits are essential in

understanding self and relating with others. When God

places us in teams, we can participate in redeeming people’s distorted view of

emotions and create environments that allow people to come with reality with

their God-given emotions

References

Anastasiadis,

Stephanos, and Anica Zeyen. 2021. “Families under Pressure: The Costs of

Vocational Calling, and What Can Be Done About Them.” Work, Employment and

Society, 095001702098098. doi:10.1177/0950017020980986.

Bandura, Albert, and Nancy

E. Adams. 1977. “Analysis of Self-Efficacy Theory of Behavioral Change.” Cognitive

Therapy and Research 1 (4): 287–310. doi:10.1007/bf01663995.

Chrobot-Mason, Donna, and Jean B. Leslie. “The

Role of Multicultural Competence and Emotional Intelligence in Managing

Diversity.” The Psychologist-Manager Journal, vol. 15, no. 4, 2012, pp, https://doi.org/10.1080/10887156.2012.730442.

Goleman, Daniel. 1997. Emotional

Intelligence. Bantam trade paperback ed. New York: Bantam Books.

Gratton,

Lynda, and Tamara J. Erickson 2007. “Eight ways to build collaborative teams.” Harvard

business review 85, no. 11 (2007): 100.

Katzenbach,

Jon R., and Douglas K. Smith. 2005. “The discipline of teams.” Harvard

business review 83, no. 7 (2005): 162.

Mayer, John D., and Peter Salovey. “What is

emotional intelligence.” Emotional development and emotional intelligence: Educational

implications 3 (1997).

Thomas, Steven L., and Wesley

A. Scroggins. “Psychological testing in personnel selection: Contemporary

issues in cognitive ability and personality testing.” The Journal of

Business Inquiry 5, no. 1 (2006).

Comments

Post a Comment